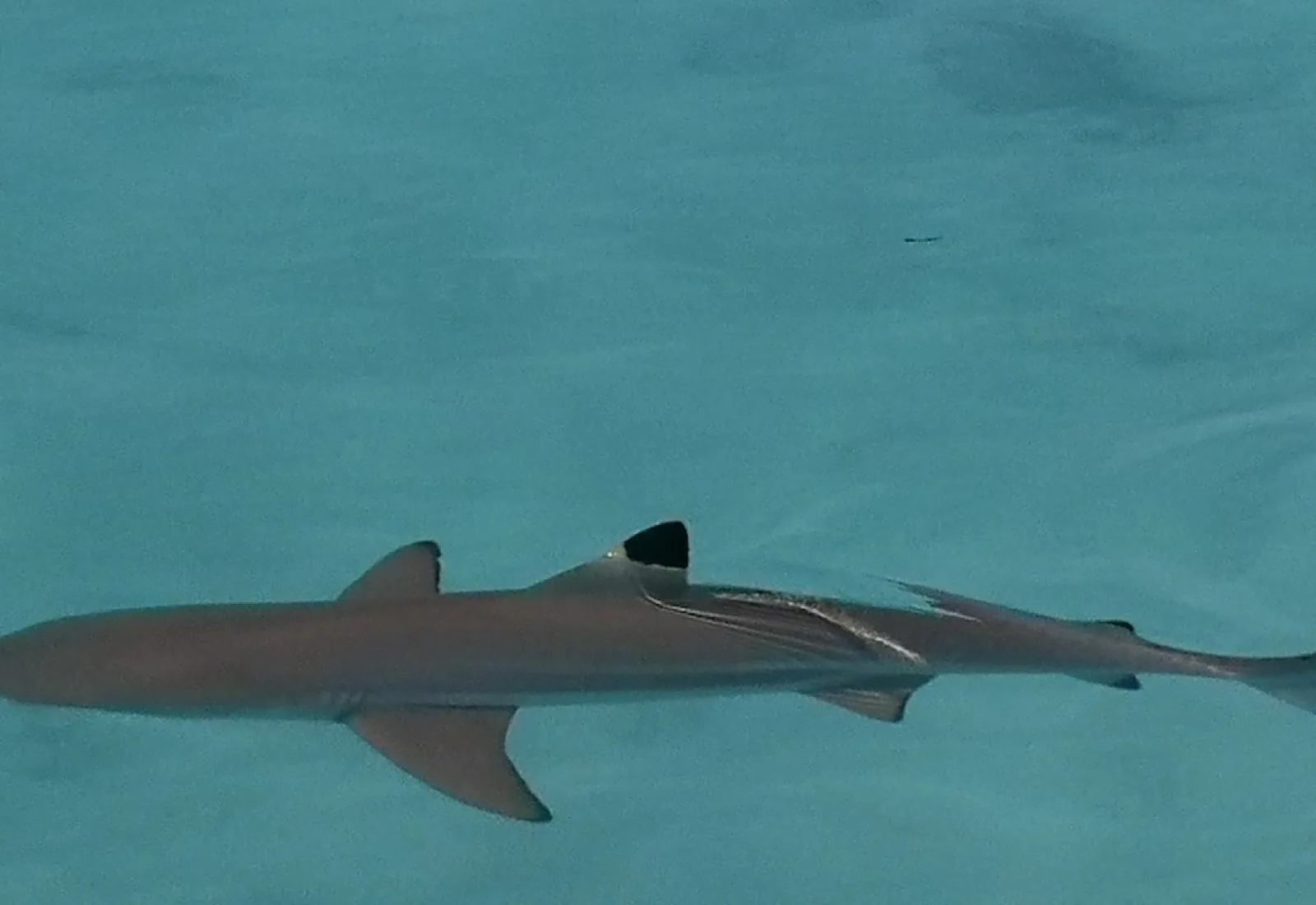

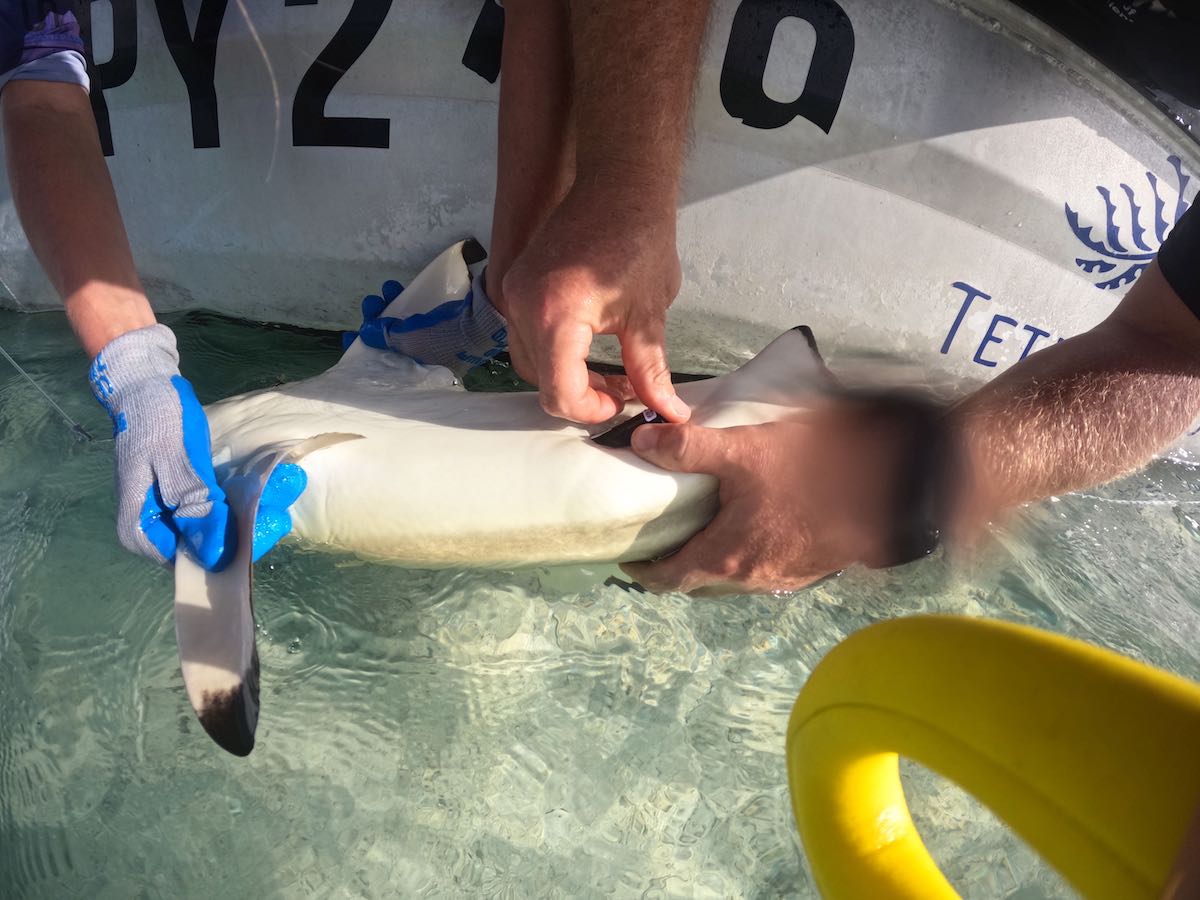

Scientists from the University of Washington led by Dr. Aaron Wirsing are continuing their work on sharks in Tetiaroa. They recently began to deploy acoustic receivers inside the lagoon that are capable of tracking tagged Blacktip Reef Sharks and Sicklefin Lemon Sharks for years to come.

Acoustic receiver deployed in the Tetiaroa lagoon

The team is working to protect sharks by better understanding their behavior and movement patterns. Their long-term study tracking sharks aims to provide a baseline of movement information that they can use to assess the impacts of future changes like warming waters, ocean acidification, coastal development, differing fisheries management scenarios, and more.

In 2020, the team contributed and published a first-of-its-kind study in Nature reporting the conservation status of reef shark populations worldwide. The results were startling; reefs sharks have become rare at numerous locations that used to be prime habitats, and in some cases, sharks may be absent altogether.

In addition to gathering baseline data on shark behavior, the team is hoping the data collected for this project will be able to answer a number of ecological questions. Including:

- Are there any 'hotspots' of shark activity?

- Do (and if so how) juveniles and adults use the lagoon differently?

- If sharks leave the lagoon, do they return in subsequent years?

- How long do juvenile sharks stay inside Tetiaroa's lagoon before potentially migrating to the nearby islands of Tahiti or Moorea?

Trackers will provide important ecological data.

They are also hoping to add supplemental receivers to expand their spatial coverage outside the lagoon in upcoming years, as well as to begin tagging efforts for other shark species (e.g., Grey Reef Sharks, Whitetip Reef Sharks). Finally, the receivers being deployed this year will be utilized by the other research projects taking place in Tetiaroa and could allow for tracking the movements of a variety of teleosts and marine reptiles.