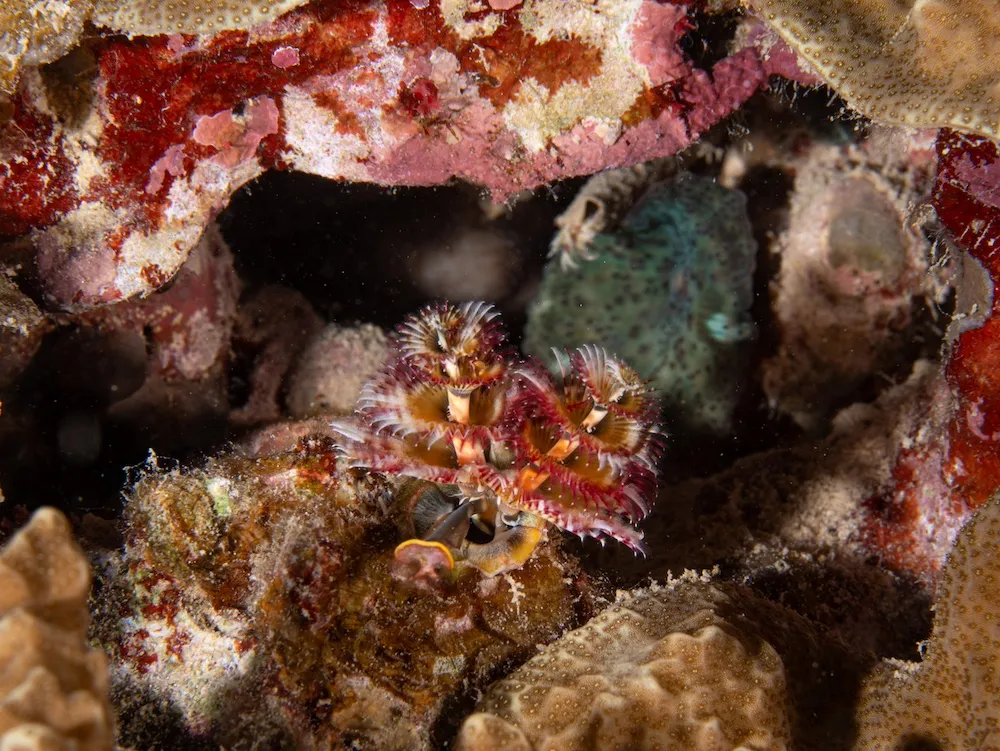

Beneath the turquoise surface of the lagoon, life thrives throughout the year. As the Christmas season approaches, these familiar residents feel especially fitting: small, colorful spirals emerging from the coral like living decorations. They are ʻEuʻa au, better known as Christmas tree worms.

Much smaller than the Christmas trees we place in our living rooms, yet just as dazzling, these tiny marine wonders light up the reefs of Tetiaroa with their spiral shapes and vibrant colors.

How to recognize them:

Red, yellow, blue, orange, white, or sometimes multicolored…

The Christmas tree worm (Spirobranchus giganteus) displays a palette worthy of a tropical Christmas market, one that still holds a touch of mystery. While some colors may be linked to protection or reproduction, the exact reasons behind this chromatic diversity remain unknown.

Its two spiral crowns, made of delicate tentacles, are used to filter plankton for feeding. At the slightest nearby movement, the worm instantly retreats into its calcareous tube, sealing the entrance with a small round operculum adorned with two distinctive “horns.” Only the spirals remain visible, its body stays hidden deep within the coral. Its larvae, tiny and translucent, first drift with the currents among zooplankton before settling on a coral, where they will spend their entire lives.

A species well established on Tetiaroa’s reefs

The Christmas tree worm has two subspecies:

- Spirobranchus giganteus giganteus, found in the Caribbean

- Spirobranchus giganteus corniculatus, found in the Indo-Pacific, including Teti’aroa

It is one of the most remarkable inhabitants of tropical reefs: a tube-dwelling worm capable of living for over 40 years without ever leaving its tube.

While it primarily settles on living corals, it can also be found on sponges, ascidians, or even bivalve shells.

A surprising symbiosis with coral

By embedding itself within the coral’s calcareous structure, the Christmas tree worm forms a fascinating relationship

- The coral provides the worm with a strong, long-lasting shelter.

- The worm, unintentionally, helps protect the coral through the constant movement of its spirals.

This motion helps deter predators such as the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci), which tends to avoid coral polyps surrounded by the worm’s vibrating plumes.

The movement also improves water circulation around the coral, delivering more nutrients to the polyps.

However, when Christmas tree worms become too abundant, they can weaken already stressed coral colonies, highlighting the fragile balance of reef ecosystems.

An essential ecological role

When a Christmas tree worm dies after several decades, it leaves behind a deep cavity in the coral. These small “abandoned homes” then become valuable shelters for other species, such as certain blennies.

Even after its disappearance, the Christmas tree worm continues to support reef biodiversity.

Here, even Christmas trees shine beneath the sea.

Photos: Theo Guillaume